An old friend of mine has had breast cancer. She hates ‘Breast Cancer Awareness Day’. Says we’re all already aware. That wearing pink means nothing. The same with that fad of turning your Facebook picture black and white (without saying why!), for ‘cancer awareness’. A while ago, she wrote a Facebook post about it that went viral. The picture she posted was a black and white selfie…of her topless, showing botched mastectomies. You could say the words she used were harsh. She said that people were already aware of cancer, and that what people need is actual help, not a bunch of black and white selfies. That the people who did it were self-serving, and wanted to feel better about themselves.

I have an odd relationship with mental health awareness days.I realise that there is a lot of work to do on stigma. However, these days don’t seem to be doing that. I once wrote:

“[mental health awareness day] seems to be an exercise in people who want to appear open and inclusive encouraging other people to have clean, sanitised convos about ‘easy to understand/relate to’ mental illnesses so everyone gets to feel smug. There, I said it.

WE DO NOT EXIST TO MAKE YOU FEEL BETTER ABOUT YOURSELF.

We are not cuddly injured puppies. We are a monstrous scary mess.”

I was feeling particularly ranty when I wrote this, but I think I have a point. These days seem to exist more for the people who support them, than the actual people with mental health problems. Additionally, where is the awareness of the ‘less palatable’ mental illnesses? I can tell you that my friends with schizophrenia, personality disorders, psychotic illnesses etc do not feel included in these days.

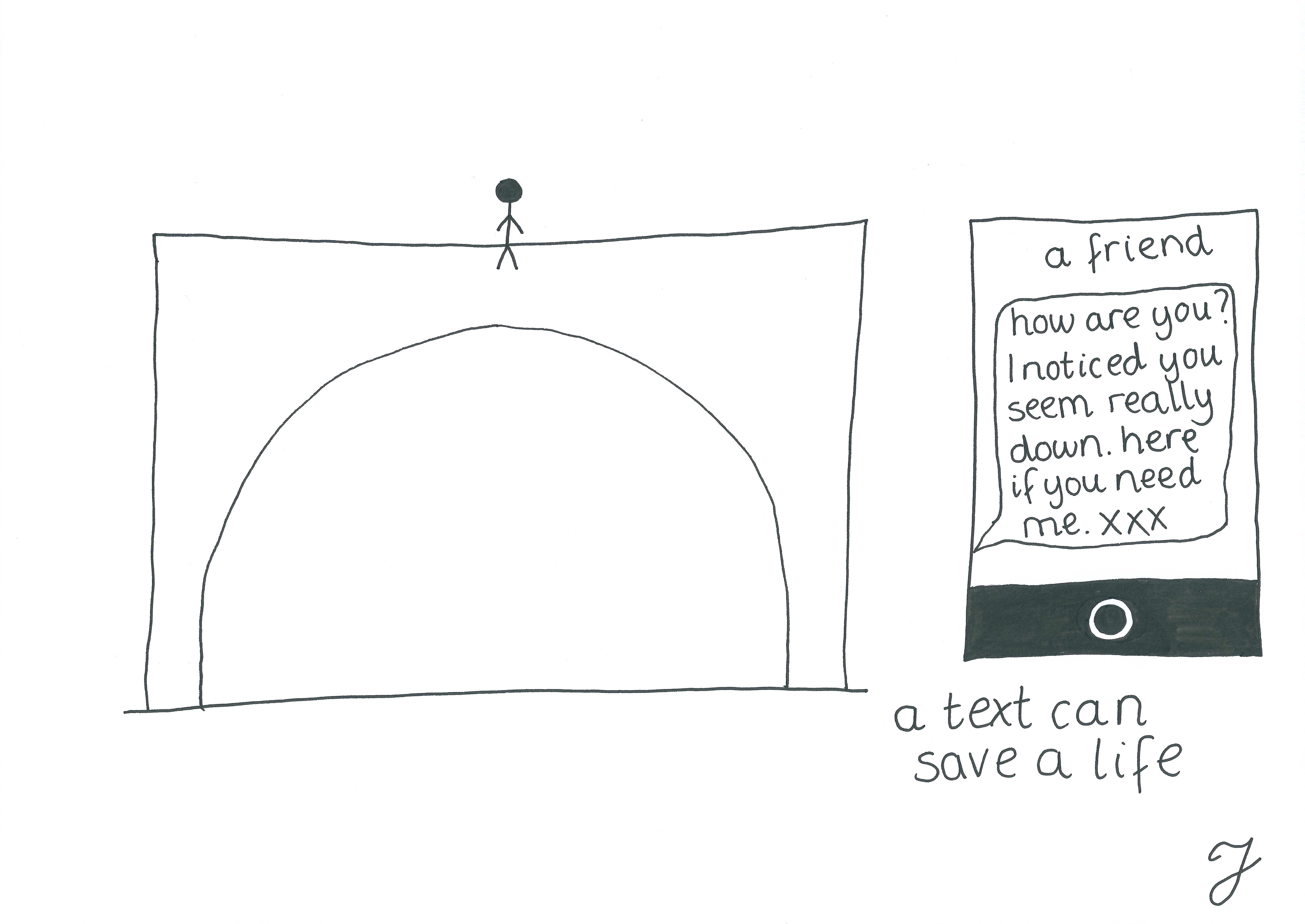

My final gripe with awareness days – they very rarely take reality into account. ‘Just ask for help’ is all well and good, but when mental health provision in no way matches the demand (for example, after several months of waiting, feeling regularly suicidal, my friend just received an appointment through to see a psychiatrist…in six months time), we have to ask ourselves how responsible that message is?

It is not a case of asking for help and accessing it at a point of crisis. The reality is long, lonely waiting times. And while I acknowledge the fantastic work of organisations like Samaritans and Breathing Space, they should be an addition to NHS services, not be expected to catch all the people failed by the system – some of whom have multiple and complex mental illnesses.

What is the answer? More NHS resources, of course. Will that happen? I’m not holding my breath, but in the meantime I’m sure there’ll be an awareness day.